Exercise to support osteoporosis management

This year, healthy bones Australia released an updated position statement regarding the use of exercise to manage osteoporosis. This position statement was developed by an expert Working Group, Advisory Committee and a National Roundtable, and was released in February (2024).

The guidelines are here if you want to check them out for yourself.

In this blog, I will go over the major recommendations in this statement, as well as those made in similar guidelines that are available for the UK and Canada (as they are all slightly different).

At FKB Physio we use a combination of these guidelines alongside clinical expertise to design our programs for osteoporosis prevention and management.

DISCLAIMER: Please do NOT undertake any of the recommendations stated in this article on your own. There is an inherent risk associated with introducing exercise when you have poor bone health. The guidelines specifically indicate that exercise MUST be done under supervision. This article is NOT designed to be taken as medical advice.

What’s osteoporosis again?

If you want a bit of a refresh about exactly what osteoporosis and osteopenia are, you can click here.

Briefly, osteopenia and osteoporosis are words that refer to poor bone health. A diagnosis is made once your bone density declines past a certain threshold. It is often only once a diagnosis of either osteoporosis or osteopenia has been made that people start to work on their bone health. Knowing that bone health essentially peaks at 30 and then slowly declines from there, it makes sense to both aim to maximise peak bone mass early in life, and work to reduce the decline in bone density associated with ageing as much as possible. This means paying attention to things that are good for bones as early as possible and continuing to do so across the lifespan.

Exercise for osteoporosis management

Exercise should always be part of osteoporotic management as medications may improve bone density but do not have any impact on reducing falls risk or sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass associated with ageing), or other impacts of osteoporosis such as loss of height and increased curvature of the upper back (hyperkyphosois). The osteoporosis guidelines specifically state that resistance training and balance exercises should be prioritised. Exercise obviously also carries some pretty significant other benefits, in that it can reduce the impacts of other co-morbidities such as high blood pressure and diabetes, among others.

Additionally, independent of the relevance to osteoporosis and bone health, the WHO specifically recommends all adults participate in strength training at least twice a week. Less than 25% of adults in Australia currently meet these recommendations. This is something that is beneficial across the lifespan and I really do believe that encouraging all adults to take up strength training in a way that is enjoyable and sustainable for them is really, really important.

Exercise for bone health recommendations

I meet a lot of people who are very active and who have done their best to lead a healthy lifestyle and they have still ended up with osteoporosis, which seems very unfair!

Remember that even with your best intentions, this condition can happen due to non-modifiable risk factors that are out of your control. I believe in trying to control the elements you can control, where possible, and it is here that having a little more information about what types of exercise are likely to be the most beneficial to the bones may be useful.

Low impact exercise, such as mat pilates, walking, swimming, and cycling, will not have a positive effect on bone density (Kistler-Fischbacher et al., 2021). This is important to note as people often assume that the resistance offered with reformer pilates as an example is adequate, however, this does not appear to be the case. Running is also unfortunately not helpful for bone density - i will discuss why later in this post.

Osteogenic loading – what is it?

Osteogenic loading refers to loading that promotes bone growth or produces bone. During movement, the skeleton undergoes force from the muscles pulling on the bone, as well as ground reaction forces. Both of these types of force cause deformation of the bone or strain on the bone, which causes microdamage that stimulates the remodelling process (Warden et al., 2021).

A particular magnitude of bone strain is required to facilitate the production of new bone (Healthy Bones Australia, 2024). It is thought that bone strain that is of a high velocity and high magnitude, that is, is large and is performed quickly causes the most significant response and consequently most significant improvement in bone health. It would seem that exposure to load also needs to be low volume (i.e. not too many repetitions) as the mechanoreceptors that detect mechanical loading of the bones become saturated quickly (Warden et al. 2021).

As such, it seems that low repetition, low volume, high intensity doses of loading are the most effective. This translates to high muscle forces, i.e. lifting heavy weights, and high ground reaction forces i.e. impact loading (jumping).

Exercises such as running, while being relatively high magnitude, are not effective due to their highly repetitive nature that lead to decreased sensitivity in the mechanoreceptors. It is also important to note that the loads required to facilitate bony adapation need to be significantly higher than those caused by activities of daily living.

Bear in mind that the studies showing these findings are primarily animal studies and as such the results need to be interpreted with caution, however when we combine these findings with other research the findings become more likely, including:

- Observational studies showing increased bone density in sports with multi directional fast loading such as tennis as opposed to those with repetitive same direction loading such as running;

- Observational studies showing runners who strength train having higher bone density than those who don’t (Wardern et al. 2014)

- Studies such as the LIFTMOR trial that show improved bone density with heavy low rep lifting in comparison to high rep light lifting (Watson et al., 2017)

We can be relatively sure that heavy lifting and high impact loading probably have some positive impact on bone health.

2024 recommendations (Healthy Bones Australia Position Statement):

1. Exercise prescription should follow general principles of osteogenic loading: The most osteogenic protocol includes low numbers of high intensity loads, including impact and resistance training

2. Exercise can reduce falls risk if performed > 3 hours per week and includes high level balance challenge.

3. Exercise for osteoporosis needs to include resistance training, balance training, and impact loading.

4. Exercise should be patient centred, with a focus more on how people can be active rather than messaging relating mostly to things that should be avoided.

5. Exercise interventions need to be tailored taking into account other co-morbidities.

The osteoporosis guidelines specifically state that resistance training needs to be progressive, which means that the weights need to progressively increase over time where possible.

These guidelines are fairly recent and quite a deviation from what was recommended historically for osteoporosis. Previously, high impact (i.e. jumping) and high intensity (i.e. heavy lifting) exercises were avoided in older adults and particularly those with osteoporosis due to the assumed risk of fracture it posed, however there have been few adverse events noted in recent studies using this type of exercise in participants with osteoporosis (Daly et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2017).

That said, it is very important that this is done progressively over time, and if any period of time is taken off exercise, it must be re-introduced very gradually again.

It is also VERY important to note that all guidelines suggest that this exercise should be supervised, as those with poor bone health do carry a higher risk of injury and as such exercise must be supervised and tailored by health professionals to minimise any adverse responses.

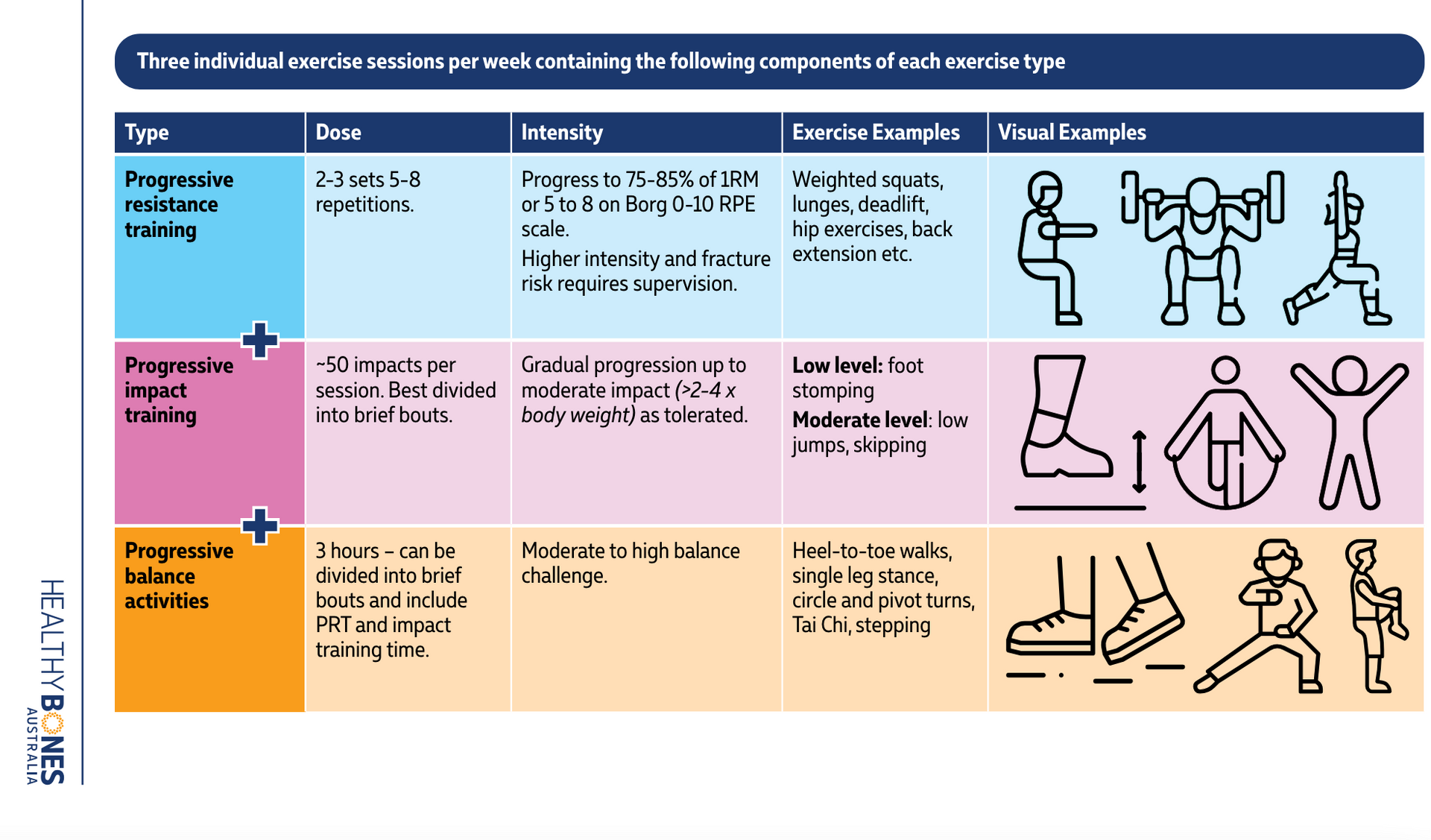

This is taken from Healthy Bones Australia website, you can find it here

Suggestion 1: Include high intensity resistance training minimum x2 per week

In this instance, the words ‘high intensity’ relate to heavy weights training. Australian guidelines for exercise for osteoporosis suggest lifting weights 75-85% of 1RM. 85% 1RM means a weight that is 85% of the weight you could only lift for one repetition, which should correlate approximately to a weight you could lift a maximum of 5-6 times. 75% 1RM is a weight you could lift about 10 times. Lifting weights at > 85% of 1RM is considered high intensity.

The recommendation in the Australian guidelines is lifting 5-8 reps for 2-3 sets at this weight. This is quite specific to our guidelines; the British guidelines suggest lifting weights of 8-12 repetitions going close towards fatigue (e.g. if instructed to lift a weight for 12 repetitions, this would be close to maximal; you would not be able to lift the weight 15 times); and the Canadian guidelines simply state it is beneficial to lift weights that progressively get heavier with no specifics around repetitions or intensity.

The number of reps prescribed in a program determines the weight – a 5 rep set should be heavier than a 12 rep set. In my experience, people dramatically underestimate the amount of weight they can lift and are hesitant to really push towards fatigue (understandably!) which means that commonly prescribing a 5 rep set will result in people lifting a weight 5 times that they really could lift for 10 reps, which isn’t really a worthwhile situation. Finding a balance between pushing towards heavier weights and lower repetitions and making sure people are actually getting a training effect from their session can be challenging and where supervision really is of benefit.

A way to check if you could possibly be lifting heavier is to check how many repetitions you are capable of doing at a given weight. So for example if you are doing 10 repetitions at a weight and don’t believe you could go any heavier, see how many reps you can do until you truly can’t do any more. If it is more than 2-3 higher than the suggested repetition range, you can probably increase the weight, but do less reps than prescribed.

E.g. you are advised to do 10 repetitions of a seated row at 20kg. You see how many reps you can do until fatigue, which is 15; so you increase the weight to 25kg, but only do 8 repetitions.

Real life application —> in our classes, we tend to use a variety of rep ranges with people. We tend to use lower reps, anywhere from 2-8 on squats and deadlifts. We use higher reps to begin with, then gradually reduce the reps as people become more confident with lifting heavier. As these exercises are usually performed first, and are amongst the biggest/hardest/use the most number of muscles, lower repetitions make sense.

We use 8-12 repetitions on exercises that are more isolated, but still cross multiple joints, such as seated rows or lunges, as this gives people more of a chance of actually reaching a degree of muscle fatigue and completing a number of repetitions at a weight that is truly hard for them. Occasionally, we include higher reps, often just for one program (6 weeks) before going down again. It is often this variety in repetitions that helps people develop a better understanding of what their body can do and keep things progressing over time.

Suggestion 2: Impact loading minimum x3 per week

Impact loading refers to jumping and leaping type of exercise. For those who are safe to do so, the guidelines suggest 50 impacts done in shorter blocks done at least 3 days per week. The guidelines state that landing with a force of 2-4x bodyweight is considered moderate impact, which is that which is experienced landing from a jump or hop. It appears that impact loading of more than 2x bodyweight is required to facilitate a bone density adaptation.

Both the British and Australian guidelines recommend this, with a recommendation of 50 impacts per day on most days if possible. Ideally, these impacts would be of varied velocity and direction - for example, 1x10 jumps on the spot, 1x10 hops on each leg, 1x10 lateral leaps side to side, 1x10 jumps forward and backwards, 1x10 jumps side to side, to maximise sensitivity of the mechanoreceptors to different types of loading.

For runners, it is recommended to leave it at least 6 hours between running and doing the jumping, as this is about how long it takes for the bone cells to ‘reset’ and become sensitive to load again (Warden et al., 2021).

Landing from a height (e.g. jumping off a step) is considered high impact and is not be recommended for those at higher risk of fracture, but may be of benefit for people without osteoporosis (Brooke-Wavell et al., 2022). The UK guidelines suggest that anyone with a vertebral fracture or a history of multiple insufficiency fractures in the lower limb should be very cautious about even moderate intensity impact loading. In this case, lower impact loading such as brisk walking is considered a safer choice.

Deciding whether to include impact loading is something to be discussed on a case by case basis with the input of a health professional. I STRONGLY DISCOURAGE anyone with any bone health concerns to take up impact loading without specific guidance.

Suggestion 3: Postural & “spine health” training

The next recommendation is around exercises that promote good strength and stability in the muscles that support the trunk. While these muscles are engaged with some of the larger exercises already described like squats and deadlifts, including some targeted movements for these muscles is reccommended, particularly to minimise increased curving of the upper back that is common with osteoporosis. The recommendation is to include these at higher repetitions, 3 sets of 10-15, a minimum of 2x per week.

In our classes, we include things such as plank holds, back extensions, overhead shoulder press, prone T lifts, prone thoracic lifts, to cover this recommendation. Essentially exercises that encourage using the upper back muscles and shoulder blade stability muscles and encourage keeping the upper back as straight as possible.

It is important to note that for many people it is NOT POSSIBLE to have a straight upper back! The upper back is naturally curved (it is called kyphosis, and it is normal). Many people have an increased kyphosis naturally, and particularly those with osteoporosis are likely to. So it is important to note that the recommendation is to TRY and keep the spine as straight as possible, to facilitate these muscles engaging, as opposed to actually keeping it straight, as this will not be achievable for many.

Suggestion 4: balance training

The next recommendation is that exercise that challenges balance can be effective in falls prevention but it must be performed 3+ hours a week to be effective. While this sounds like a lot, it is important to note that lots of things count as exercise to improve balance. For example, performing lunges, or jumps, counts as balance exercise, as they involve a reduced base of support, and working to control a landing. Strength exercise also is beneficial in improving balance, generally.

For people at particularly high risk of falling, introducing some more specific balance exercises like walking forward/backward/ standing on one leg/ etc may be of benefit, more benefit than to people who are at a higher level of function. This is because it is unlikely that they are performing exercises targeting other areas (strength, cardio etc) that are challenging enough to benefit their balance.

Suggestion 5: patient centred

Finally, as obvious as it sounds, it is important for exercise to be tailored to the individual. We are always dealing with people who have concurrent diagnoses such as pelvic floor dysfunction, osteoarthritis, neurological conditions, injuries, post surgeries, etc, that mean these recommendations need to be tailored.

There is always a starting point, and an entry point, to exercise, for every body.

At FKB Physio we pride ourselves on being able to figure out what works for you and gradually build from that point. If you are interested in getting started, book an initial appointment with any of our physios.

- Beck, B. R., Daly, R. M., Singh, M. A., & Taaffe, D. R. (2017). Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport, 20(5), 438-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.10.001

- Beck, B. R. (2022). Exercise Prescription for Osteoporosis: Back to Basics. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 50(2), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1249/jes.0000000000000281 https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3865

- Brooke-Wavell K, Skelton DA, Barker KL, et alStrong, steady and straight: UK consensus statement on physical activity and exercise for osteoporosisBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2022;56:837-846.

- Daly, R. M., Gianoudis, J., Kersh, M. E., Bailey, C. A., Ebeling, P. R., Krug, R., Nowson C. A., Hill, K., & Sanders, K. M. (2020). Effects of a 12-Month Supervised, Community-Based, Multimodal Exercise Program Followed by a 6-Month Research-to-Practice Transition on Bone Mineral Density, Trabecular Microarchitecture, and Physical Function in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res, 35(3), 419-429. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3865

- Kistler-Fischbacher, M., Weeks, B. K., & , B. R. (2021). The effect of exercise intensity on bone in postmenopausal women (part 1): A systematic review. Bone, 143, 115696. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2020.115696

- Kistler-Fischbacher, M., Yong, J.S., Weeks, B.K. and Beck, B.R. (2021), A Comparison of Bone-Targeted Exercise With and Without Antiresorptive Bone Medication to Reduce Indices of Fracture Risk in Postmenopausal Women With Low Bone Mass: The MEDEX-OP Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res, 36: 1680-1693. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.4334

- Morin SN, Feldman S, Funnell L, Giangregorio L, Kim S, McDonald-Blumer H, Santesso N, Ridout R, Ward W, Ashe MC, Bardai Z, Bartley J, Binkley N, Burrell S, Butt D, Cadarette SM, Cheung AM, Chilibeck P, Dunn S, Falk J, Frame H, Gittings W, Hayes K, Holmes C, Ioannidis G, Jaglal SB, Josse R, Khan AA, McIntyre V, Nash L, Negm A, Papaioannou A, Ponzano M, Rodrigues IB, Thabane L, Thomas CA, Tile L, Wark JD; Osteoporosis Canada 2023 Guideline Update Group. Clinical practice guideline for management of osteoporosis and fracture prevention in Canada: 2023 update. CMAJ. 2023 Oct 10;195(39):E1333-E1348. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.221647. PMID: 37816527; PMCID: PMC10610956.

- Osterhoff, G., Morgan, E. F., Shefelbine, S. J., Karim, L., McNamara, L. M., & Augat, P. (2016). Bone mechanical properties and changes with osteoporosis. Injury, 47 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1383(16)47003-8

- Rajaei A, Dehghan P, Ariannia S, Ahmadzadeh A, Shakiba M, Sheibani K. Correlating Whole-Body Bone Mineral Densitometry Measurements to Those From Local Anatomical Sites. Iran J Radiol. 2016 Jan 27;13(1):e25609. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.25609. PMID: 27127575; PMCID: PMC4841932.

- Watson, S. L., Weeks, B. K., Weis, L. J., Harding, A. T., Horan, S. A., & Beck, B. R. (2018). High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 33(2), 211-220. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3284

- Warden SJ, Davis IS, Fredericson M. Management and prevention of bone stress injuries in long-distance runners. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Oct;44(10):749-65. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2014.5334. Epub 2014 Aug 7. PMID: 25103133.

- Warden SJ, Edwards WB, Willy RW. Preventing Bone Stress Injuries in Runners with Optimal Workload. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2021 Jun;19(3):298-307. doi: 10.1007/s11914-021-00666-y. Epub 2021 Feb 26. PMID: 33635519; PMCID: PMC8316280.

- Hinton, P. S., Nigh, P., & Thyfault, J. (2015). Effectiveness of resistance training or jumping-exercise to increase bone mineral density in men with low bone mass: A 12-month randomized, clinical trial. Bone, 79, 203-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bone.2015.06.008